If you are one of the millions of Americans taking a bisphosphonate drug for treatment of bone loss, you’ve most likely worried about what you’ve gotten yourself into.

If you are one of the millions of Americans taking a bisphosphonate drug for treatment of bone loss, you’ve most likely worried about what you’ve gotten yourself into.

Earlier this month, the FDA took the highly unusual step of publishing the results of their investigation into reports of atypical fractures of the femur occurring in long term users of drugs like Fosamax (alendronate), Actonel (risedronate), Boniva (ibandronate) and Reclast (zoledronic acid).

Now we have yet another investigation confirming the association of these fractures with bisphosphonate use, and correlating the increasing risk with increasing duration of therapy.

When categorized by duration of treatment, compared with no treatment, the odds ratio for an atypical fracture vs. a classic fracture were 35.1 for less than two years of treatment, 46.9 for two to five years of treatment, 117.1 for five to nine years and 175.7 for more than nine years.

What’s Going On Here?

How do drugs that are supposed to prevent fractures cause new ones? That’s a good question. And the answer is complicated, so let’s see if I can simplify it.

Think of your bones as a road system that is constantly being remodeled depending on where the traffic is. There’s a large well-funded road crew constantly digging up the old road and replacing it with new road. They work in small sections scattered throughout the system, so as not to disrupt the road’s integrity. The members of the crew that digs up the old road are called the osteoclasts –

and the ones who fill in and re-pave it are called the osteoblasts.

and the ones who fill in and re-pave it are called the osteoblasts.

Now suppose over time, for whatever reason – age, bad weather (underlying medical conditions), lack of road material (vitamin D deficiency, menopause) – you’ve dug up or lost more roads than you’ve replaced (Osteoporosis). So you start treatment with a bisphosphonate like Fosamax or Actonel or Boniva. These drugs work by cutting back on the digging crew, but keeping the paving and refilling going in the areas that have already been dug up, thus rapidly bringing miles and miles of untravelable road into good use. Not to mention it’s a nice strong road, becoming mineralized over time. (That’s your bone density increasing.)

The whole thing is working so well that you send almost the entire road crew on a prolonged vacation. (Suppression of bone turnover, which is how bisphosponates work) Now you’re left with a skeleton road crew (pun intended), which, for most folks is still enough to deal with the usual cracks and potholes that appear over time, and can keep the road (your bones) in good working condition. But in some of you (perhaps those who are genetically predisposed) the downsized crew just can’t keep up with the repair work. As time goes on, the structural integrity of your bones becomes weakened. And then one day, for no apparent reason, just during the course of usual activity, a small crack that the crew hasn’t yet repaired becomes a large crack – and you’ve just fractured your femur.

You don’t have to be on a bisphosphonate for these kind of atypical fractures to occur. Some folks just get them. But taking a bisphosponate increased the chances in predisposed individuals, and that chance increases the longer you take the drug, especially if your bone mass is in the osteopenic or normal range.

Exactly What are the Risks?

The chance that you’ll get one of these atypical spiral fractures while taking bisphosphonates is extremely low – one study estimates the incidence at about 32 per million users per year, compared with over 10 times that many fractures prevented in the same million users. So overall, the benefits of these drugs still far outweigh the risks.

However, drilling down into the fracture data reveals that we can do better than just accepting a rare risk in return for a common benefit.

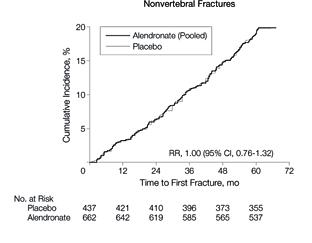

Those who develop atypical fractures appear to be individuals whose bone mass in the femur is in the normal or osteopenic range, as opposed to those whose hips show osteoporosis. This happens to be the very same group that recent studies suggest may safely stop Fosamax after 5 years without losing the benefits of having been on the drug.

So, if continuing the drog for longer than 5 years adds little benefit but increases risks, even if those risks are rare, it becomes pretty darned obvious what we need to do. Stop the drug.

Which reminds me of that song from Kenny Rogers – “You got to know when to hold ’em / Know when to fold ’em / Know when to walk away /Know when to run… ” Not that treating osteoporosis is a gamble, but the Gambler’s advice rings eerily true for this class of drugs.

When to Fold ‘Em

New data suggest that as long as your bone density is above the osteoporotic range, you can stop taking your bone meds after 5 years. Continuing the drug past that time only brings added risk without any benefit.

When to Hold ‘Em

If you’re at increased risk for fracture and have been taking your meds for less than 5 years, you may still be getting benefit without significant risk. Remember that these drugs decrease the risk of conventional osteoporotic fractures at over 10 times the rate that they increase the risk of atypical fractures, so don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. But make sure you are getting adequate vitamin D, calcium and weight bearing exercise to maximize the benefits you’re getting while you’re still on these drugs. And discuss with your doctor whether its worth considering coming off the drug in the future if your bone mass improves into the osteopenic range.

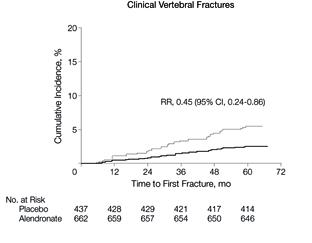

If you’ve been on these drugs for 5 years or more, but your bone mass is still in the osteoporotic range, you also may still be getting benefit from continuing treatment. Ditto if you’re at high risk for vertebral fractures. You are not in the group at highest risk for atypical fractures, but are in the group at highest risk for the more common type of osteoporotic fractures. Talk to your doctor about the comparative risks of continuing vs stopping treatment. It may not be a straightforward decision, as we don’t have exactly clear guidance on when to stop in everyone. But at least have the conversation.

Should You Even Be in the Bisphosphonate Game?

Not everyone taking bisphosphonates needed to start them in the first place. Aggressive marketing and disease mongering by Big Pharma initially led to overuse of these drugs for treatment of osteopenia, a condition we now know does not necessarily need to be treated. With the help of the FRAX fracture risk calculator, we’re now able to determine which patients with osteopenia are at significant fracture risk and require treatment (very few, it turns out) and which ones can be adequately managed with lifestyle, calcium and vitamin D (most). Talk to your doctor about using FRAX before deciding if treatment is warranted.

Remember too that bisphosphonates are not the only drugs that treat osteoporosis. Other medications to consider include hormone replacement, Evista (raloxifene) and injectable terapeptide. Each of these drugs has its own set of risks and benefits, and some work better than others depending on your type and location of bone loss, so a reflex switch from bisphosphonates may not necessarily be the best option. As always, its best to talk with your doctor about what is right for you.

Bottom Line

The optimal duration of bisphosphonates for most individuals appears to be between 3-5 years. Beyond that point, unless there is osteoporosis at the hip or a high spinal fracture risk, there appears to be added risk rather than additional benefit to prolonged use of these medications, and it may be time to consider stopping therapy.

__________________________________________________________

Resources

- Ott, Susan. What is the Optimal Duration of Bisphosphonate Therapy? Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine September 2011 vol. 78 9 619-630. A must read for prescribers of bisphosphonate therapy.

- Meier RH, Perneger TV, Stern R, Rizzoli R, Peter RE. Increasing occurrence of atypical femoral fractures associated with bisphosphonate use Arch Intern Med. Published online May 21, 2012. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1796.

- Whitaker M, Guo J, Kehoe T, Benson, G, et al. Bisphosphonates for Osteoporosis — Where Do We Go from Here? New England Journal of Medicine. Published online May 9, 2012.

- Black DM, Bauer DC, Schwartz AV, et al. Continuing Bisphosphonate Treatment for Osteoporosis — For Whom and for How Long? New England Journal of Medicine. Published online May 9, 2012. Doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1202623

- Bridget M. Kuehn. Studies Probe Possible Link Between Bisphosphonates and Femoral Fractures JAMA. 2010;303(18):1795-1796. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.576

However, there was a significantly higher risk of vertebral fractures in women who stopped aledronate.

However, there was a significantly higher risk of vertebral fractures in women who stopped aledronate.

Mrs. O’Leary Milking Daisy by Norman Rockwell

Mrs. O’Leary Milking Daisy by Norman Rockwell